What is the Capital Stack?

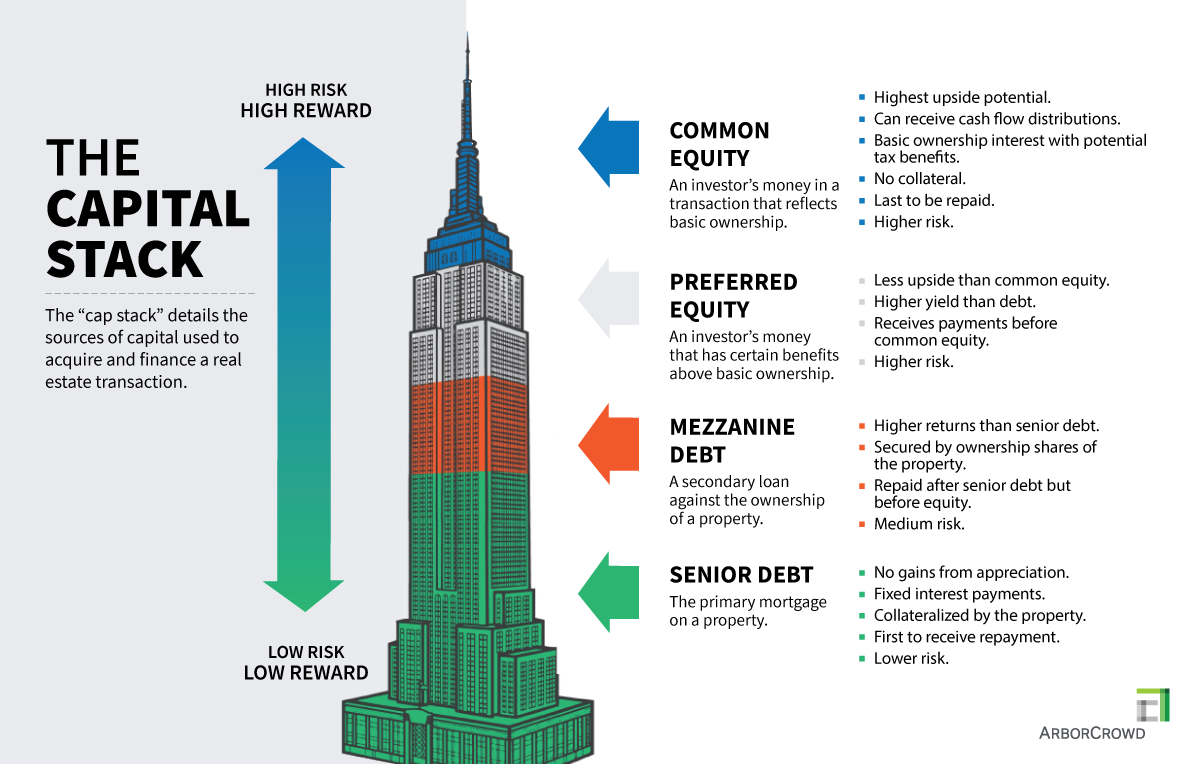

Real estate investment firms obtain capital from various sources to acquire and finance deals. This capital comes in the form of either debt from financial institutions, or equity investments from a variety of investors or the sponsor themselves. The funds used in a real estate transaction are arranged in different tranches, which forms the capital stack. The capital stack, comprised of debt and equity, is organized (or “stacked”) based on the varying levels of risk and priority of the funds used in the transaction.

Most real estate capital stacks contain common equity and a senior debt position, but some transactions are more complex, and may contain mezzanine debt or preferred equity tranches of capital as well. Each tranche of the capital stack has distinct nuances that impact their return potential.

Senior Debt’s Place in the Capital Stack

Senior debt (or the first mortgage) is the tranche with the highest priority in the capital stack. The holders of senior debt are the first to be paid on any deal, and they receive interest payments on the loan made to the borrower as well as the repayment of the loan principal upon maturity of the debt.

Additionally, senior debt holders have the lowest risk in an investment as the loan is secured by a mortgage on the property. If there’s a default on the debt service payments, the senior debt holder can take ownership of the property through foreclosure.

Since senior debt holders have the lowest risk, they typically have the lowest return potential. They are limited to returns from the fixed or floating rate loans, and will not receive returns from the appreciation of a property’s value.

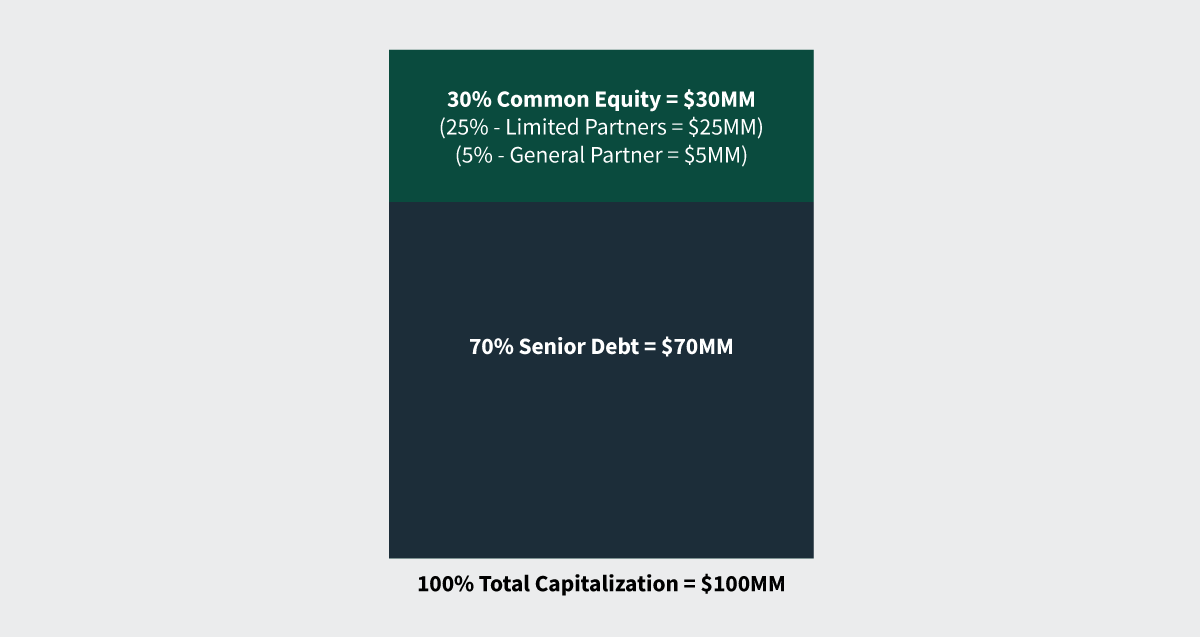

The terms of senior debt and the size of the loan, which is typically anywhere from 50% to 75% of the total capital stack, could depend on a combination of the risk level of the deal, the quality of the sponsor, and various market factors.

Sponsors use senior debt to maximize potential returns. It is important to pay attention to the level of leverage used on a transaction, because the more debt involved, the riskier the deal could be to investors. Even if the property isn’t performing as expected, the sponsor must repay the debt in accordance to the loan agreement. Having too much debt (also known as being overleveraged) could lead to the equity being wiped out in a foreclosure due to the sponsor’s inability to pay the required debt service.

Below is a hypothetical example of the capital stack of a $100 million real estate deal that contains only common equity and senior debt:

Mezzanine Debt’s Place in the Capital Stack

As noted above, senior debt will typically not exceed 75% of the total cost of the property and certain additional costs. However, in some cases, sponsors do not want to contribute 25% of equity to fund the remainder of the capital stack. This may be because they don’t have access to enough funds or because they prefer to utilize higher leverage, which allows them to deploy the capital they do have across more deals.

In either case, the sponsor could borrow a second layer of capital called mezzanine debt. Mezzanine debt has a subordinate position to the senior debt and a priority position to the common equity, meaning that mezzanine debt holders will receive payment before equity investors but after senior debt holders.

Although mezzanine debt is a loan, it is not collateralized by the underlying property. Instead, it is secured by a pledge of the borrower’s ownership interests in the property owner. If the borrower under a mezzanine loan defaults, the mezzanine lender could utilize a UCC foreclosure and take over the ownership of the property owner.

While effectively, this means that the mezzanine lender becomes the property owner, they are still subject to the full senior debt and the associated mortgage payments (unlike a senior lender that gets full ownership of a property upon a foreclosure without being subject to any outstanding loans). Because mezzanine lenders have more risk than senior lenders in a deal, mezzanine lenders will charge higher interest rates. However, the mezzanine debt holders’ upside is typically capped at that rate (similar to how the senior debt holders’ upside is capped).

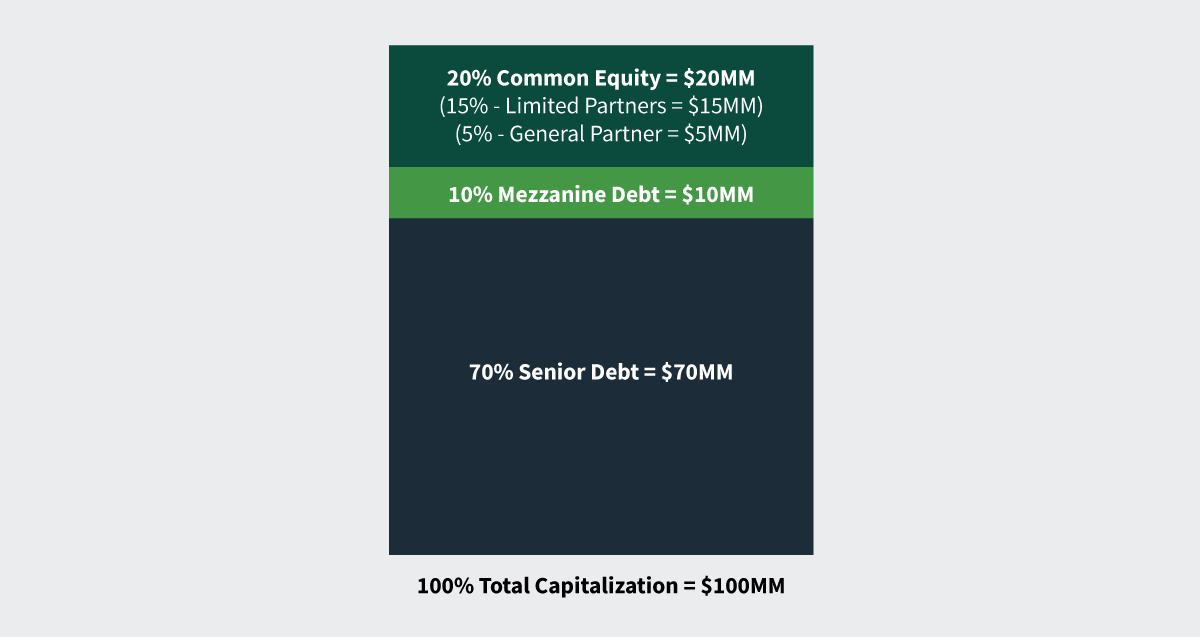

To explain how mezzanine debt can be used, in the prior example of a $100 million real estate deal, assume that instead of $30 million of common equity, only $20 million of common equity is used and the $10 million balance is borrowed via a mezzanine loan:

By adding a mezzanine debt tranche to the capital stack, the sponsor is able to take $10 million of equity out of the deal – which can be deployed in another transaction – and the increased leverage allows the common equity holders to earn a higher levered return if the deal is successful, compared to a deal with only senior debt or an all-cash deal.

As previously mentioned, increasing the overall leverage of a deal can expose common equity investors to increased risk of losing their investment if the deal performs poorly. Furthermore, a deal with higher leverage from mezzanine debt is more at risk from swings in values of the underlying real estate. Using the example from above, if the property lost 25% of its value due to market fluctuations, the common equity investors with just 20% interest in the property can be foreclosed on by the mezzanine lender. If the capital stack did not include a mezzanine lender, the same dip in value would not necessarily wipe out the common equity from the investment.

Preferred Equity’s Place in the Capital Stack

Preferred equity, sometimes referred to as “pref equity,” is often viewed as a hybrid between debt and equity. Preferred Equity holders typically have priority for distributions and return of capital events over the common equity, however, they are subordinate to the senior debt position in the transaction.

Preferred equity holders may have the right to receive income distributions from interest reserves, or their interest may accrue until paid, even if the property is not cash flowing. Therefore, preferred equity holders may have less risk compared to common equity investors, albeit for typically less upside potential if the property outperforms.

Fixed redemption dates for preferred equity holders are common, and the outstanding preferred equity balance must be repaid regardless of property cash flow. Preferred equity can be utilized to maximize returns for common equity investors, and like mezzanine debt, it may also be a viable option to close a gap in financing if a sponsor is unable to secure the amount of debt required to refinance or acquire an asset.

Preferred equity investments aren’t collateralized by the underlying real estate like senior debt investments. Instead, they are more similar to mezzanine loans; if certain defaults occur, preferred equity holders may have the right to take management and ownership control of the entity that owns the underlying real estate from common equity holders, in many cases, completely wiping out the common equity holders’ value in the transaction.

Also, like mezzanine debt, upon taking control of the property-owning entity, the preferred equity holders would still be subject to the senior loan and would be required to cover the debt service payments.

Common Equity’s Place in the Capital Stack

Common equity typically carries the greatest risk in the capital stack compared to other positions, but it also has the greatest upside potential if the underlying investment performs well. Common equity investors have ownership interests in the real estate and could lose their entire investment if the deal is unsuccessful, or if the sponsor defaults on the mortgage loan used to finance the project. Additionally, equity holders are the last to be paid distributions from cash flow or capital transactions.

However, common equity investors share in the appreciation of the value generated by the realization of the property, in addition to potential cash flow distributions over the hold period.

The common equity position in a deal is typically comprised of general partner and limited partner equity positions. The general partner, which is usually the sponsor, is responsible for sourcing the deal, obtaining financing, managing the project, and negotiating with buyers to realize the deal. Limited partners are typically passive investors and don’t make day-to-day operating or managing decisions.

General and limited partners agree to a distribution “waterfall,” which dictates how returns will be distributed between the equity investors. General partners usually could earn a larger portion of the returns – called a “promote” – after certain predetermined return thresholds are reached for limited partners. This is viewed as a positive factor for limited partners, because it incentivizes the sponsor to maximize the performance of the deal.

Prior to investing in deals, investors should understand the different nuances associated with each layer of the real estate capital stack as well as the potential risks and rewards they can offer.